A question of life and death

Roughly shaped and small objects like miniature vessels or ceramic toy animals and wagon wheels fitting into children’s hands are their traits in the archaeological record. Besides, children’s graves and the finds they contain reflect best the sorrow caused by losing a child. The so-called nursing bottles found in the graves of some small children attest to the care mothers have given to their babies for millennia, while the milk residues detected in samples taken from such vessels indicate that they may have had a role in weaning. Whole eggs and eggshells were probably placed in the graves of children and women as a symbol of rebirth and hope (Pictures 1). Joint graves of parents and their children or brothers and sisters and protective and apotropaic amulets in the grave are also marks of the love and anxiety of the parents for the deceased child and the power of the family bond.

Some grave findings in the burials of juveniles and children may reflect that, in social terms, children entered adulthood relatively early. For example, some believe that in the Avar Period, the right to wear a belt adorned with pressblech (decorated with pressed patterns), later cast metal mounts, was bound to coming of age.

Personal grave finds can reflect the identity of the deceased. Accordingly, weapons were usually interred with men, while women’s graves contain jewellery items and the equipment of spinning and weaving. Besides, some professions, like a metalsmith or a shaman, can also be identified from a grave assemblage.

Weapons and pieces of armour in the grave of a woman or a child do not mean we have found ‘amazons’. Women in the Avar Period strung pieces of armour in their necklaces or kept them in their purses hanging from the belt for protection. Artificial cranial deformation served more than aesthetic purposes, probably marking social position, ethnicity, or family ties.

- Dual burial of a mother and her child in the Scythian Period cemetery of Soroksár-Akácos

- Skull of a Hun man from District 14, Vezér Street, and its facial reconstruction (by Ágnes Kustár and Sándor Évinger – Hungarian Natural History Museum)

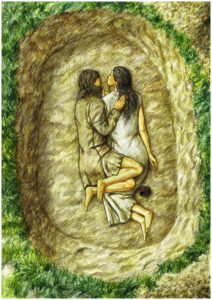

- Flexed woman and man in a common grave on the Neolithic site at District 11, Október huszonharmadika Street

- Reconstruction of the dual burial on the Neolithic site at District 11, Október huszonharmadika Street (graphics by Erzsébet Csernus)

- CT image of a chainmail fragment corroded onto other items (an iron knife and a cicada brooch) from a woman’s grave in the Early Avar Period cemetery unearthed at District 22, Növény Street (by Affidea Magyarország Ltd Diagnostic Centre, Orsolya Kangyal)

- Dual burial of probably a woman and a girl in the Avar Period cemetery of District 22, Növény Street